Before the Kindle, Nook, and iPad, there was the Palm

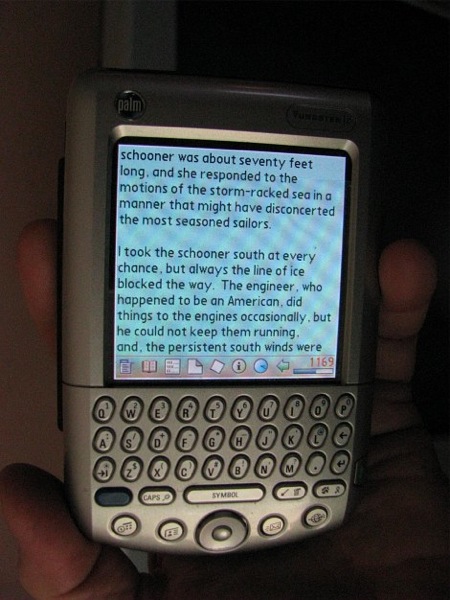

I got my Palm some years ago, to help out my fibromyalgia-diminished memory. It was like a proto-tablet, on which I could take notes, write, outline, draw and paint well enough to illustrate notes, and keep a calendar and to-do list. There were all sorts of games for it, and apps to change the look of the interface. The one feature I thought I’d never use was the ability to read entire books on that tiny screen.

But it came loaded with a mystery by a popular author and, compulsive reader that I am, I took a look at it and found it quite easy to read. Fonts and font size were adjustable and later I got a third-party app that enabled me to change the background color to one my eyes found more comfortable. I’ve been reading on my Palm ever since.

It’s a small device, about the size of a pack of cards, and with an upgraded memory card it can easily hold 50 or 75 books in addition to all the other stuff. iSiloX, companion app to one of the readers, would convert text files to Palm format (.pdb), so all of Project Gutenberg was mine.

Like most people, I don’t find it pleasant to read text continuously on the computer screen for an hour, and I would never have printed out these copyright-free books, but to have them available to read any time I wanted on the Palm—that worked for me. Is it easier to concentrate my visual attention on the small screen than on the large one? I don’t know what the reason is, but reading the Palm is more comfortable for long periods whether by daylight or in a dark room.

Some of what I’ve been reading in the wee hours

Although I’ve bought a few e-books and issues of sf magazines for the Palm, mostly I have read my way through free downloads, 19th and early 20th C. works from Jack London’s social fiction and reflections on his own alcoholism, to Virginia Woolf’s Common Reader essays. I’ve found several good reads among women writers including novels like Wives and Daughters (1865), and North and South (1854), by Elizabeth Gaskell, and excellent short stories by Edith Wharton, Willa Cather, Mary Austin, and Katherine Mansfield. The Woman Who Did (1895) by Grant Allen, is about a “New Woman” who dared to live her life as she wished, having an affair but refusing to marry the man, raising the child, with tragic results. Then there’s the wide range of popular adventure fiction, of which I’ve enjoyed works by such out-of-fashion writers as H. Rider Haggard, P. C. Wren, and Ouida, with titles like The Snake and the Sword, and Under Two Flags (both stories of the French Foreign Legion). All these have been enjoyable to read in themselves, and of course provide fascinating windows into life and attitudes, with the same sort of caveats that attach to judging our times by our popular fiction.

I’ve got some familiar big-C Classics on the Palm too, like Fagles’s recent translation of the Odyssey (a purchased e-book, I have it in print as well), Northanger Abbey and Tom Jones (haven’t been able to finish either one of these), a couple of Anthony Trollope novels (more readable, enjoyed The Warden), and a bunch of poetry. There’s a goodly selection of older sf to be found online as text files, and even some new sf books that have been made freely available by authors such as Cory Doctorow.

Views of Antarctic heroism, and of the world before ours

Just now my 2 am reading is Sir Ernest Shackleton’s South, his account of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition (1914–17)—often known as the “ill-fated” Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Their sturdy ship was trapped in pack ice for nearly a year, then crushed by the movement of the ice; the men lived on ice floes for some time since the current was taking them closer to land, but when the floes broke up under their feet, they took to 3 small open boats…and on it goes. The privation endured, the courage and resourcefulness shown, are astonishing. One aspect of human beings at their best.

Replica of one of the expedition’s open boats, among pack ice.

And here too, are found glimpses of how differently some things were perceived.

Shackleton’s ship the Endurance left England just after the outbreak of what was to become World War I; at the time many thought it would be over by Christmas. I just read the part where Shackleton and a few companions reach South Georgia Island, having left the rest of the company slowly starving on Elephant Island, while they cross 800 miles of ocean in a small boat in order to send back a rescue ship. They are forced to land on the opposite side of the island from Stromness Whaling Station, and Shackleton takes the two fittest men on a 36-hour trek over glaciers and rocky peaks, without a map, to reach “civilization”.

The first thing Shackleton says to the whaling station manager, after introducing himself, is “Tell me, when was the war over?” It is May, 1916, and he cannot conceive that the war might still continue. The manager replies, “The war is not over. Millions are being killed. Europe is mad. The world is mad.” Later, after arranging for the other two men on South Georgia to be picked up, Shackleton and a companion hear details of the war. “We were like men arisen from the dead to a world gone mad,” he says.

I’ve often read of how shocked and demoralized people of the time were by this unprecedented industrialized war that dragged on and on, by the use of poison gas, machine guns, long-range artillery, and planes, and by battles such as the Somme, in which over one million men (on both sides) were killed, wounded, or taken prisoner, over a 4 and 1/2 month period. British casualties on the Somme (in these same three categories) were 80% during that time; by November, 80% of the original men in a division were gone save for those lightly wounded who returned. The total advance of the Allied lines was 8 miles.

But this scene, in which men in such an isolated and inhospitable place learn all at once of the war, has a different imaginative impact. After all, the late 20th-century reader may be appalled by the Somme, but knows already of things as bad or worse: the Holocaust, Rwanda, visions of nuclear war. To imagine Shackleton learning about his time’s Great War suddenly, in one conversation, is to experience a little of how it was for those of his time.

Many well-educated young men with literary leanings joined up in 1914, and some of them wrote poetry while in camps and trenches. The early World War I poetry is of a high idealistic tenor probably not equalled by any war poetry since, because that war changed reality for everyone then and since. Never again, I hope, can anyone write something like this, about dead soldiers:

Blow out, you bugles, over the rich Dead!

There’s none of these so lonely and poor of old,

But, dying, has made us rarer gifts than gold.

These laid the world away; poured out the red

Sweet wine of youth; gave up the years to be

Of work and joy, and that unhoped serene,

That men call age; and those who would have been,

Their sons, they gave, their immortality.

First stanza of 1914 III: The Dead by Rupert Brooke.

As I recall, Brooke died just as his attitude toward the war began to shift from public-school “play the game” patriotism to something more hopeless and grim. But many another British war-poet showed this change of reality that took place for his generation and those to come, including us. Things were never the same. Though it is long, I’ll reprint here one such poem:

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame, all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys! — An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime. —

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin,

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs

Bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues, —

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

The poem is Dulce et Decorum est, by Wilfred Owen, written in 1915.

Dulce et decorum est, pro patria mori (Latin) means “It’s sweet and fitting to die for one’s country”. This famous quotation from Horace would have been extremely familiar to public-school boys, in that time when education always included the Latin language and literature as well as some indoctrination about the Empire. In 1913, the first line, Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori, was inscribed on the wall of the chapel of the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst (Wikipedia), and the text and the sentiment were used to encourage enlistment and support of the war.

Indeed, Ernest Shackleton and his men (not one perished, incredibly) did emerge from the ice-bound wilderness “like men arisen from the dead” into a world forever changed.

Detail from John Singer Sargent, Gassed (1918). This painting hangs in the Imperial War Museum in London; the canvas is over seven feet high and twenty feet long. It depicts soldiers blinded by gas being led in lines back to the hospital tents and the dressing stations; the men lie on the ground all about the tents waiting for treatment. (Source)

Mine is the same response as any soldier’s hallow would be, sheaves of wheat to be woven into love, vineyards for the soul to embrace and dance to, a candle of beeswax in a hovel before a field needing to be cleared of rock, the deep sorrow of my mother’s womb, me striding undaunted toward a wicker balustrade with a thread of light to be woven there.